“Privilege” is a word you’ll hear often in social justice spaces, both offline and online.

Some people understand the concept easily. Others – and I was like this – find the concept confusing and need a little more help.

If you’re willing to learn about privilege, but you don’t know where to start, you’ve come to the right place!

Before we get started, I want to clarify that this article is not entirely comprehensive. That is to say, it’s not going to explain everything there is to know about privilege. But it’ll give you a good foundation on the basics.

Think of privilege not as a single lesson, but as a field of study. To truly understand privilege, we must keep reading, learning, and thinking critically.

Defining Privilege

The origins of the term “privilege” can be traced back to the 1930s, when WEB DuBois wrote about the “psychological wage” that allowed whites to feel superior to black people. In 1988, Peggy McIntosh fleshed out the idea of privilege in a paper called “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies.”

We can define privilege as a set of unearned benefits given to people who fit into a specific social group.

Society grants privilege to people because of certain aspects of their identity. Aspects of a person’s identity can include race, class, gender, sexual orientation, language, geographical location, ability, and religion, to name a few.

But big concepts like privilege are so much more than their basic definitions! For many, this definition on its own raises more questions than it answers. So here are a few things about privilege that everyone should know.

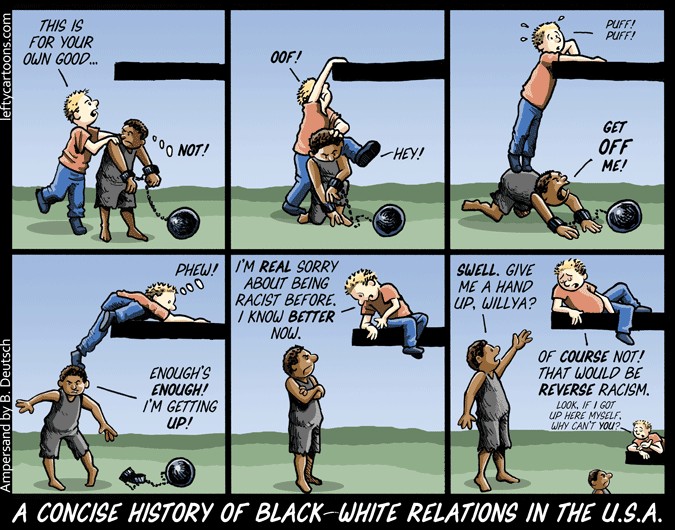

1. Privilege is the other side of oppression.

It’s often easier to notice oppression than privilege.

It’s definitely easier to notice the oppression you personally experience than the privileges you experience since being mistreated is likely to leave a bigger impression on you than being treated fairly.

So consider the ways in which you are oppressed: How are you disadvantaged because of the way society treats aspects of your identity? Are you a woman? Are you disabled? Does your sexuality fall under the queer umbrella? Are you poor? Do you have a mental illness or a learning disability? Are you a person of color? Are you gender non-conforming?

All of these things could make life difficult because society disenfranchises people who fit into those social groups. We call this oppression.

But what about the people society doesn’t disenfranchise? What about the people society empowers at our expense? We call that privilege.

Privilege is simply the opposite of oppression.

2. We need to understand privilege in the context of power systems.

Society is affected by a number of different power systems: patriarchy, white supremacy,heterosexism, cissexism, and classism — to name a few. These systems interact together in one giant system called the kyriarchy.

Privileged groups have power over oppressed groups.

Privileged people are more likely to be in positions of power – for example, they’re more likely to dominate politics, be economically well-off, have influence over the media, and hold executive positions in companies.

Privileged people can use their positions to benefit people like themselves – in other words, other privileged people.

In a patriarchal society, women do not have institutional power (at least, not based on their gender). In a white supremacist society, people of color don’t have race-based institutional power. And so on.

It’s important to bear this in mind because privilege doesn’t go both ways. Female privilege does not exist because women don’t have institutional power. Similarly, black privilege, trans privilege, and poor privilege don’t exist because those groups do not have institutional power.

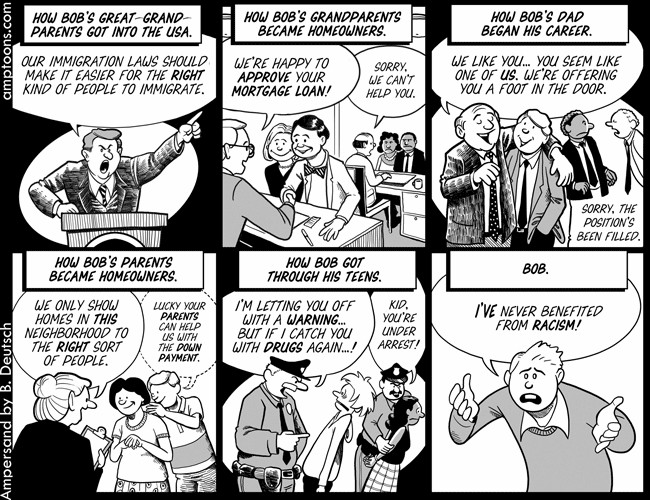

It’s also important to remember because people often look at privilege individually rather thansystemically. While individual experiences are important, we have to try to understand privilege in terms of systems and social patterns. We’re looking at the rule, not the exception to the rule.

3. Privileges and oppressions affect each other, but they don’t negate each other.

I experience my queerness in relation to my womanhood. I experience these aspects of my identity in relation to my experience as a mentally ill person, as someone who’s white, as someone who is South African, as someone who is able-bodied, as someone who is cisgender.

All aspects of our identities – whether those aspects are oppressed or privileged by society – interact with one another. We experience the aspects of our identities collectively and simultaneously, not individually.

The interaction between different aspects of our identities is often referred to as anintersection. The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, who used it to describe the experiences of black women – who experience both sexism and racism.

While all women experience sexism, the sexism that black women experience is unique in that it is informed by racism.

To illustrate with another example, mental illness is often stigmatized. As a mentally-ill woman, I have been told that my post-traumatic stress disorder is “just PMS” and a result of me “being an over-sensitive woman.” This is an intersection between ableism and misogyny.

The aspects of our identities that are privileged can also affect the aspects that are oppressed.Yes, privilege and oppression intersect — but they don’t negate one another.

Often, people believe that they can’t experience privilege because they also experience oppression. A common example is the idea that poor white people don’t experience white privilege because they are poor. But this is not the case.

Being poor does not negate the fact that you, as a white person, are less likely to become the victim of police brutality in most countries around the world, for example.

Being poor is an oppression, yes, but this doesn’t cancel out the fact that you can still benefit from white privilege.

As Phoenix Calida wrote:

“Privilege simply means that under the exact same set of circumstances you’re in, life would be harder without your privilege.

Being poor is hard. Being poor and disabled is harder.

Being a woman is hard. Being a trans woman is harder.

Being a white woman is hard, being a woman of color is harder.

Being a black man is hard, being a gay black man is harder.”

Let’s look at the example of people who are both poor and white. Being white means that you have access to resources which could help you survive. You’re more likely to have a support network of relatively well-off people. You can use these networks to look for a job.

If you go to a job interview, you are more likely to be interviewed by a white person, as white people are more likely to be in executive positions. People in positions of power are usually the same race as you, so if they are racially prejudiced, it’s likely that they would be prejudiced in your favor.

A poor black person, on the other hand, will not have access to those resources, is unlikely to be of the same race as people in power, and is more likely to be harmed by racial prejudice.

So once again: Being white and poor is hard, but being black and poor is harder.

4. Privilege describes what everyone should experience.

When we use the word “privilege” in the context of social justice, it means something slightly different to the way it’s used by most people in their everyday environment.

Often we think of privilege as “special advantages.” We frequently hear the phrase, “X is a privilege, not a right,” conveying the idea that X is something special that shouldn’t be expected.

Because of the way we use “privilege” in our day-to-day lives, people often get upset when others point out some of their privileges.

A male acquaintance of mine initially struggled to understand the concept of privilege. He once said to me, “Men don’t often experience gender-based street harassment, but that’s not a privilege. It’s something everyone should expect.”

Correct. Everyone should expect to be treated that way. Everyone has a right to be treated that way. The problem is that certain people aren’t treated that way.

To illustrate: Nobody should be treated as if they are untrustworthy based on their race. But often, people of color – particularly black people – are mistrusted because of prejudice towards their race.

White people, however, don’t experience this systemic, race-based prejudice. We call this “white privilege” because people who are white are free from racial oppression.

We don’t use the term “privilege” because we don’t think everyone deserves this treatment.

We call privilege “privilege” because we acknowledge that not everyone experiences it.

5. Privilege doesn’t mean you didn’t work hard.

People often get defensive when someone points out that they have privilege. And I totally understand why – before I fully understood privilege, I acted the same way.

Many people think that having privilege means you have had an easy life. As such, they feel personally attacked when people point out their privilege. To them, it feels as if someone is saying that they haven’t worked hard or endured any difficulties.

But this is not what privilege means.

You can be privileged and still have a difficult life. Privilege doesn’t mean that your life is easy, but rather that it’s easier than others.

I saw this brilliant analogy comparing white privilege and bike commuting in a car-friendly city, and it inspired me to broaden the analogy to privilege in general.

So let’s say both you and your friend decide to go cycling. You decide to cycle for the same distance, but you take different routes. You take a route that is a bit bumpy. More often than not, you go down roads that are at a slight decline. It’s very hot, but the wind is at usually at your back. You eventually get to your destination, but you’re sunburnt, your legs are aching, you’re out of breath, and you have a cramp.

When you eventually meet up with your friend, she says that the ride was awful for her. It was also bumpy. The road she took was at an incline the entire time. She was even more sunburnt than you because she had no sunscreen. At one point, a strong gust of wind blew her over and she hurt her foot. She ran out of water halfway through. When she hears about your route, she remarks that your experience seemed easier than hers.

Does that mean that you didn’t cycle to the best of your ability? Does it mean that you didn’t face obstacles? Does it mean that you didn’t work hard? No. What it means is that you didn’t face the obstacles she faced.

Privilege doesn’t mean your life is easy or that you didn’t work hard. It simply means that you don’t have to face the obstacles others have to endure. It means that life is more difficult for those who don’t have the systemic privilege you have.

So What Now?

Often, people think that feminists and social justice activists point out people’s privilege to make them feel guilty. This isn’t the case at all!

We don’t want you to feel guilty. We want you to join us in challenging the systems that privilege some people and oppress others.

Guilt is an unhelpful feeling: It makes us feel ashamed, which prevents us from speaking out and bringing about change. As Jamie Utt notes, “If privilege guilt prevents me from acting against oppression, then it is simply another tool of oppression.”

You don’t need to feel guilty for having privilege because having privilege is not your fault: It’s not something you chose. But what you can choose is to push back against your privilege and to use it in a way that challenges oppressive systems instead of perpetuating them.

So what can you – as a person who experiences privilege – do?

Understanding privilege is a start, so you’ve already made the first move! Yay!

There’s a great deal of information out there on the Internet, so I’d firstly recommend that you read more about the concepts of oppression and privilege in order to expand your understanding. The links in this article are a good place to start.

But merely understanding privilege is not enough. We need to take action.

Listen to people who experience oppression. Learn about how you can work in solidarity with oppressed groups. Join feminist and activist communities in order to support those you have privilege over. Focus on teaching other privileged people about their privilege.

Above all else, bear in mind that your privilege exists.

* The article is by Sian Ferguson

Source of image: No greater joy.